SyQuest Drives

SyQuest Drives

Removable Drive

MacWeek January 5, 1988

The earliest trace of what would become a juggernaut in late-80s/early-90s Macintosh storage was an article in MacWeek in late November, 1987:

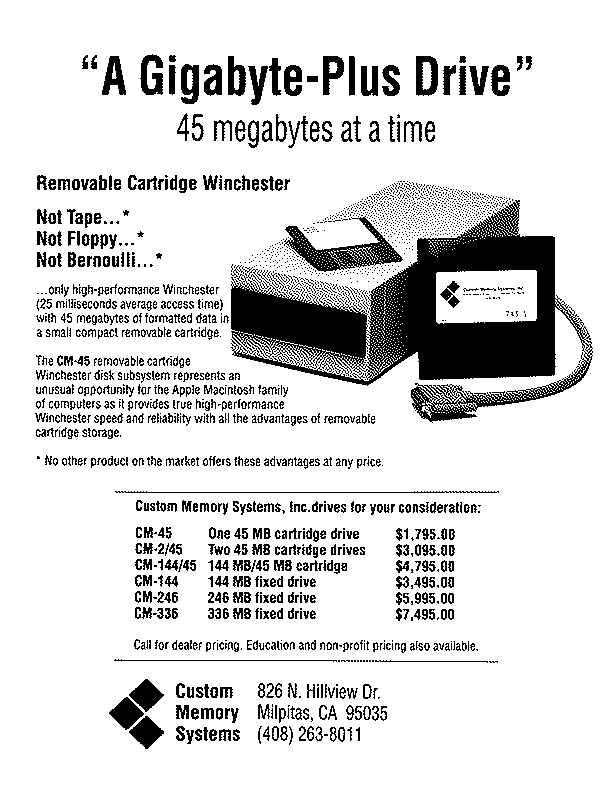

MILPITAS, Calif. — Custom Memory Systems Inc. has announced a December ship date for a removable hard disk drive system for the Macintosh. The $1,795,5.25 half-height drive, the CM-55, has an average access time of 25 milliseconds and a 1-to-l interleave — the same performance offered by many hard disks. It stores data on 44.5-Mbyte removable cartridges that are available from the company for $125 each. The CM-55 takes about 10 seconds to come to speed after a cartridge is inserted and automatically tests each cartridge during the process, according to the company. Custom will include software utilities with the drive that will help users configure their system of disks.[…]

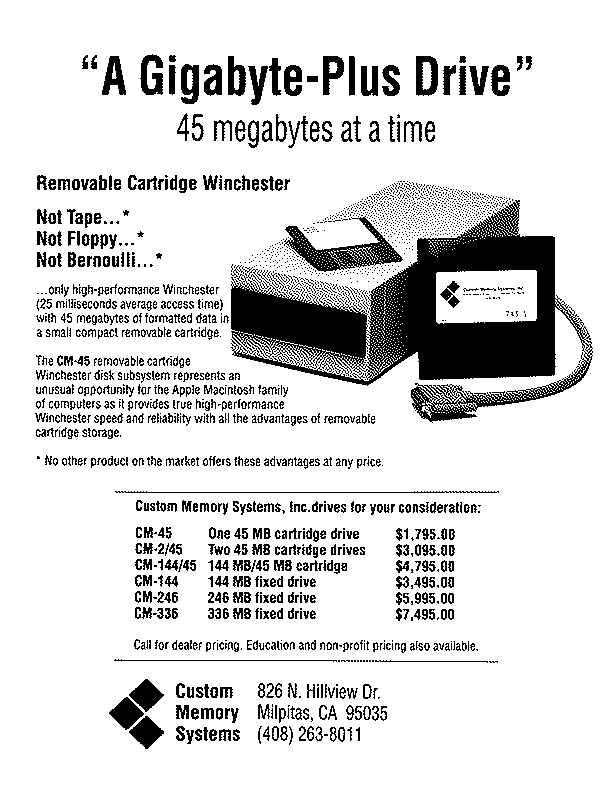

In late 1987 CMS was still the exclusive retail partner for SyQuest’s technology — although that would soon change. The name SyQuest didn’t show up in any early CMS publicity material; the company initially tried to brand the new device and its cartridge “CM-55” (The number referred to the unformatted capacity of each cartridge; in actual use of course the capacity was 44 megabytes and CMS’s first ads show a change to “CM-45.”) Nevertheless, SyQuest would become shorthand for the entire system, with that company’s logo appearing on nearly every cartridge sold.

If CMS was determined to play down the OEM manufacturer in these early days, MacWeek reporter Jiri Weiss did the opposite. He dug up a fascinating pre-history of the company — one that did not exactly inspire confidence. Despite having delivered nearly $50 million worth of earlier drives to the federal government and large corporations, Syquest’s technology suffered from a design flaw which occasionally locked cartridges to only working with the exact drives they were first used in:

The company that developed the technology, Syquest Technology of Fremont, Calif., has had problems with reliability in the past, said Phil Devin, senior industry analyst with Dataquest, a market research firm in San Jose, Calif. The problem has been to design cartridges so that they are interchangeable, Devin said. With data packed in closer than on a floppy, it is easy for the drive to miss Track 0, the disk directory, he said. “Even sealed drives have had problems finding Track 0. When you play with hard-track densities, it becomes very hard to design a reusable pack,†he said. Although Syquest has had return rates of 20 percent on earlier models, the problems were solved several years ago, Steve Katamay, CMS president, said. “I wouldn’t have put the earlier models in my product. The disks are now 100-percent interchangeable.â€

Also interesting from this November 1987 MacWeek article is that CMS executives were already anticipating the competition that SyQuest would be measured against — the Mac version of the VHS/Betamax debate: “The closest thing to this is a Bernoulli drive, but we are as far above it as a hard disk is above a floppy.” (Bernoulli drives were manufactured by Utah-based Iomega, whose later product Zip would become the SyQuest drive of the mid-1990s.) CMS’s first full-page ad, shown above, was explicit: “Not Tape… Not Floppy… Not Bernoulli.”

MacWeek predicted customer shipments for the CM-55 in December 1987, for an introductory retail price of $1,500 which would soon ramp up to $1,800 (!) for the drive alone. 44meg (sorry, “55 megabyte (unformatted)” cartridges would be $125 each. In retrospect, these early prices seem astronomical — by the time the original 44mb system had hit its stride and achieved large scale deployment, drives would go for for $200 and cartridges $40.

But what need would drive the success required for a successful transition from niche to necessity? In a word: the laser parlor. An essential (if now vanished) element of the 1980s Desktop Publishing scene, these retail operations offered walk-in access to high-end printing equipment that the average user could never afford. Although as time went on some offered professional-class imagesetters with dedicated outboard RIPs (raster image processors), in the early years many provided nothing more than access to an Apple LaserWriter Plus or IINT. The $5-$8,000 price point of these early laser printers — although inexpensive compared to even a few years previous — still rendered them inaccessible for the average freelance designer or page layout artist. (We are still a few years before the 1989 introduction of the HP DeskWriter and its democratization of pseudo-300dpi output.) So the solution was simple: take your PageMaker or Adobe Illustrator files into a facility where you could print out your work in high resolution, and perhaps have it duplicated at the same time for mass distribution.

In order to do that, you needed to fit your work on an 800k disk. Easy enough for a simple vector illustration, or a text-heavy DTP project. But what about large, multi-page projects with complicated EPS and large scanned TIFFs? And how to assure that the laser parlor would have the precise fonts you designed with — which, keep in mind, were licensed only to you? Juggling multiple floppy disks to dynamically reassemble a complex project, when laser parlors were charging by the hour as well as the page, would be frustrating and expensive. And in the days before a reasonably-priced laptop (the $7,000 Macintosh Portable cost more than a laser printer), bringing in your entire workstation would be a literal heavy lift.

Enter the SyQuest cartridge. With 44 megabytes of space, even the largest and most complex desktop publishing project would fit, with room to spare for the outline and screen fonts, linked external TIFFs, precise version of PageMaker or Quark with all the needed plugins — even your own System Folder, if you wanted to boot directly from the cartridge itself. Years before the NeXT Cube and its magneto-optical drive would become widely available, the SyQuest 44mb system offered the real-world, affordable experience of what Steve Jobs promised in the introduction of that futuristic computer: bringing your entire data world with you in a portable disk.

Unlike the black Cube’s rather over-engineered technology (lasers at two different intensities, to either read the magnetic disc or write to it by heating each bit to the Curie point), the SyQuest system was simple: essentially an externalized magnetic hard drive platter, encased in a rugged semi-translucent plastic rectangle and reasonably sealed to keep out dust while in transit. Upon inserting the cartridge, the drive drew open a black plastic arc of a door, inserting its read/write heads above and below the disk as it entered. A characteristic “clicking” spin-up sound followed, accompanied by a flashing light that cycled from orange to green as the drive became ready. Once loaded, the disk was easily as fast as the average internal or external hard drive in most cases (a refreshing contrast to the magneto-optical drive NeXT used, whose speed was so slow the company began to ship traditional 40mb “caching” drives to bolster the systems’ reaction times.)

SyQuest escaped the orbit of its first reseller, CMS, with a second deal with Mass Micro in January 1988. :

MacWeek January 26, 1988

and asserts its own brand as it becomes a must-have peripheral, available from vendors such as MassMicro, Jasmine, Microtech, and others. Meanwhile, the earliest mention I can find of SyQuest in a user context is an August 1988 column from BMUG’s David Morgenstern in MicroTimes. Morgenstern usually wrote a summary of the latest news and gossip drawn from the weekly BMUG meetings, so it’s safe to say that SyQuest had become a big topic of conversation during the summer of 1998:

One of the favorite new toys of the Mac power-users with power-bucks are the 44 meg “removable media” drives. These are hard-disk drives with the hard-disk in a removable plastic cartridge. They are the 10-wheel truck of Floppyville. All of the hardware manufacturers are coming out with some form of these drives. D.P.I, MassMicro and Peripheral Land have been leading the pack with big ad budgets.

Interesting is that David never mentions “SyQuest” brand name in his piece — apparently the large size of the removable storage (44MB) was a better descriptor than the OEM vendor of the actual mechanism.

MacWorld magazine first mentioned SyQuest drives in the context of a Backup article in November 1988. Given print magazines’ lead times — and the complexity of an article that reviewed 50 separate products — it’s safe to say this also reflects a Summer 1988 timeframe for the transformation of SyQuest: from newly-introduced gadget to essential accessory.

Posted in Hardware | No Comments »

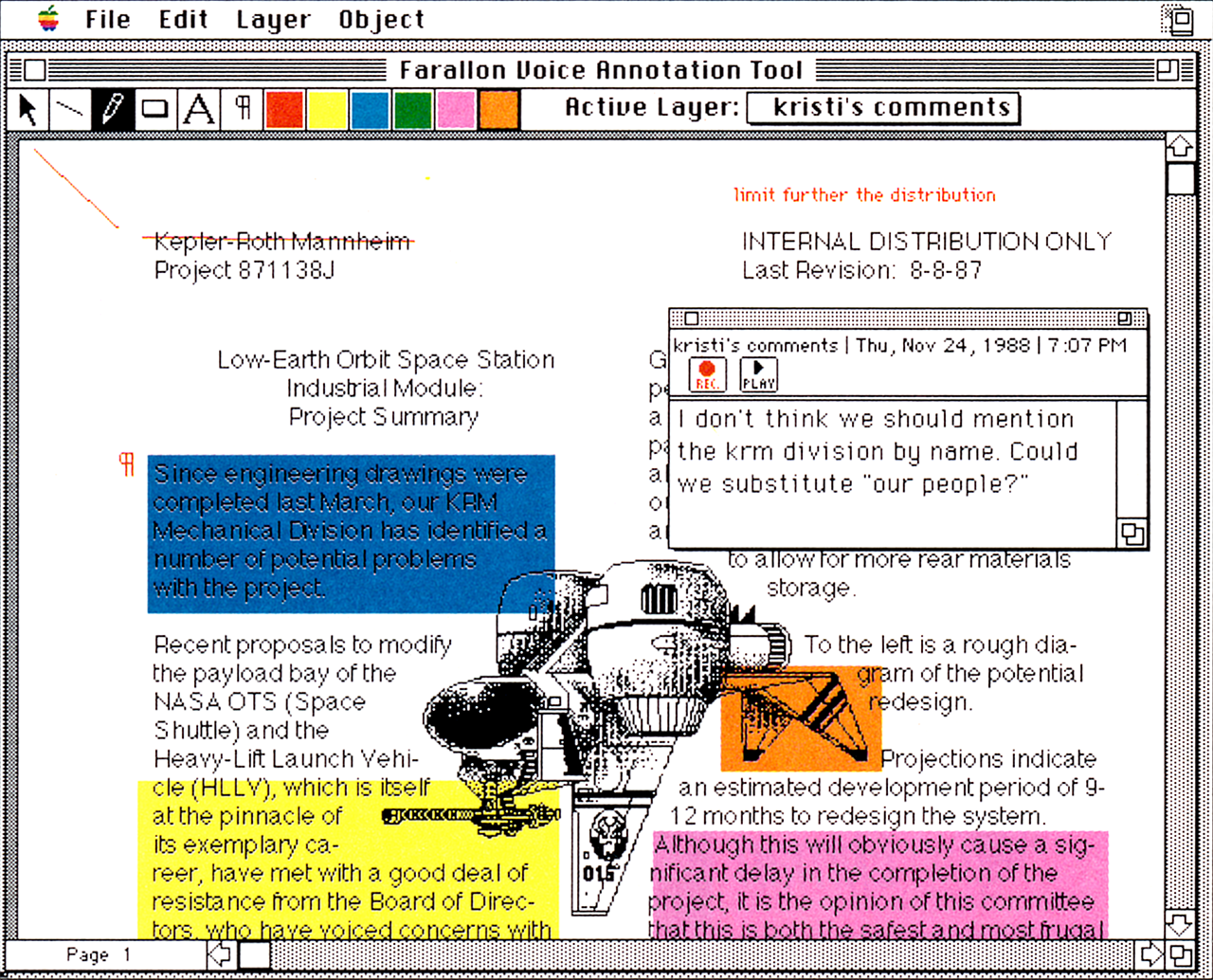

Farallon DiskPaper

Farallon DiskPaper