Radius Full Page Display

1,294 words

13K on disk

September 1986

Radius Full Page Display

Radius Full Page Display

Two screens are better than one

We often remember March 1987 as the start of the era of external displays on the Macintosh. With the enormous size of the Mac II came expandability of six NuBus slots, as well as the software flexibility of System Software 2.0 (System 3.3/Finder 5.4) with the Monitors control panel.But large additional monitors actually predated the “open Mac” by a good half-year.

In October 1986, Macworld magazine heralded “The Two-Headed Macintosh” in a story that highlighted Apple veterans Burrell Smith and Andy Hertzfield’s contributions to this new combination of hardware and software. The magazine was excited about two features: the near-match to the internal screen’s 72dpi, and the possibility of using both the new and the old screen simultaneously. Both the article itself and the caption to the accompanying press photograph (reproduced above) highlighted the ability to move windows freely between the two screens in a new kind of virtual two-dimensional space. All the standard software niceties that would become hallmarks of Radius’ premium experience make their debut here — detachable, “tear-off” menus that could be repositioned anywhere on the screen; a larger font size for those menus; a screen dimmer, and control over the size of the cursor to reduce the possibility of losing the mouse in such a large field of vision.

Enabling all this took a new Motorola 68000 processor — perhaps running at a higher clock frequency? — that completely replaced the Mac’s original CPU. A requirement of “the new Macintosh ROM” meant that this product was restricted to Mac Plus and 512kE models, which would have been clear to any Mac Pro in 1986. And the price? A mere $2,000 — two thirds as much as any Mac in which it could be installed. The November issue of MacUser gave the entire cover over to the new display, proclaiming “Bigger is Better!” Wikipedia goes so far as to call the Full Page Display the “first large screen available for any personal computer.”

Looking at this picture you probably have two questions: How could this possibly have made sense financially? How could this possibly have worked technically?

Hardware

The second question is easy enough to answer. Radius was made up of ex-Apple hardware engineers, and they pulled quite a few rabbits out of their collective hat. The FPD used the security slot, of all possible things, to route the cable for external video out of the case. Notice the small video connector in the photo to the right:

The second question is easy enough to answer. Radius was made up of ex-Apple hardware engineers, and they pulled quite a few rabbits out of their collective hat. The FPD used the security slot, of all possible things, to route the cable for external video out of the case. Notice the small video connector in the photo to the right:

This was was routed through the small security slot on the back of the classic Mac case. The Full Page Display interface sat right on top of the 68000 central processor, with additional connections to the FB1 and C35 resistors. Originally this internal card originally had to be installed in the Sunnyvale factory, and the process took a week to complete. An easier clip-on installation method was released in Q2 1987.

Permanent changes to the motherboard were also made. These presumably included the Radius ROM, which obviated the need for a special boot-up disk – a requirement of other vendors’ solutions. The integration between the Radius ROM and the Apple motherboard was evidently pretty deep: as an example, the larger PRAM in a Mac Plus allowed the precise vertical alignment between the tops of the internal and external screens to be memorized, but the 512KE had to be set manually at every boot time.

The Economics of Desktop Publishing

The financial question is more interesting. Who was spending $2,000 to add an external monitor onto a Mac Plus — let alone a 512KE?

The portrait display as a form factor, though gone from the market today, actually was quite popular in the late 80s and early 90s. The reason was simple: as the name implied, it could display a full 8.5×11 page on the screen at one time with its 640×864 pixels. This was in an era of Aldus PageMaker: Desktop Publishing was saving the entire Mac ecosystem (and arguably Apple) from being a footnote in computing history.

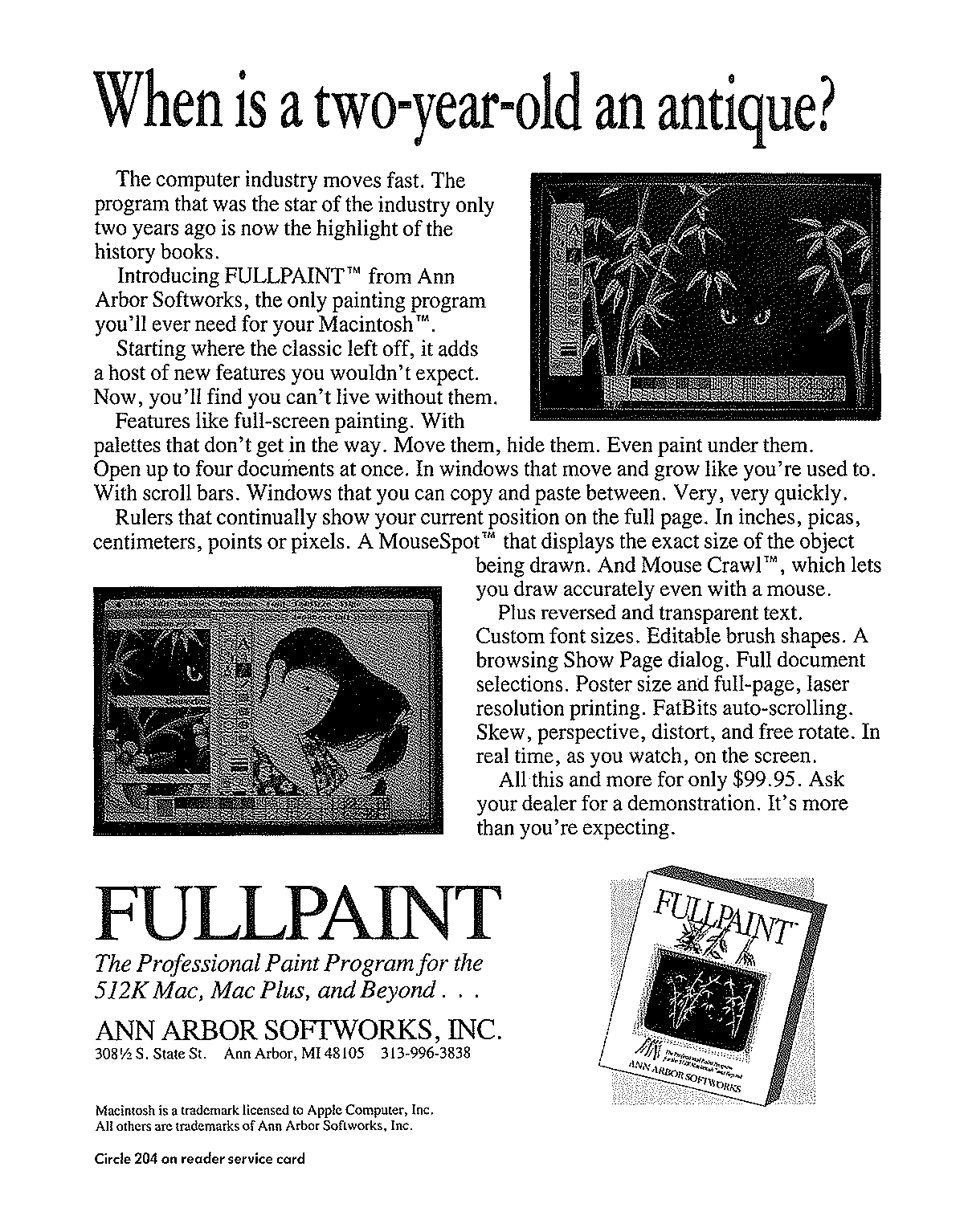

There are two interesting things about this FPD ad from 1988:

The first is that the LaserWriter Plus flanks the monitor to the left: Radius envisioned the FPD as an essential part of a complete DTP setup. The second is that there’s a humble classic Mac to the right. Even in 1988, when the Mac II had been shipping for a while (notice the picture of that expandable machine lower in the ad copy), Radius still saw a market in upgrading Classic Macs with external displays for the Desktop Publishing market.

The Shock of Multiple Screens

At 15″ diagonally, the FPD had nearly the same 72 dpi pixel density as the Mac CRT, a big selling point. In fact, Radius was the only player in this nascent market who could actually use both screens at the same time. Other vendors, including E-Machines and Micrographic Images, shut down the internal screen completely. This simultaneous use of both workspaces, which we all take for granted today, was as revolutionary as capacitive touch was in 2007. “As the mouse reaches the right- hand edge of the Radius, the image suddenly appears on the Mac’s screen, jumping right across the gulf between the two machines,” gushed InfoWorld. “This behavior invariably startles people the first time they see it.” Here’s Stewart Cheifet being startled this feature during a demo by Radius co-founder Mike Boich on Computer Chronicles:

Of course, application compatibility was hit-and-miss. Even an app as canonical and central to the Macintosh as MacPaint wasn’t written to take advantage of the greater screen space. Excel would crash if you made the window too large, and MacWrite wouldn’t properly redraw the screen after formatting changes which extended off the original 512×342 pixels. Updates fixed some of these problems, but there was a reason that Radius demo’d the screen with T/Maker’s WriteNow: it was written according to the guidelines in Inside Macintosh and worked well. Raines Cohen, co-founder of the Berkeley Macintosh Users Group, saw the display at MacWorld Boston 1986 and noted “The Finder doesn’t know about the Macscreen, but can use the entire Radius. MacPaint doesn’t know about it, of course; FullPaint does, sort of, I think… SuperPaint will let you put your pallette at top of the screen to take advantage of MOST of the screen. ComicWorks is the best; it lets you put your tools onthe Mac screen & dedicate the whole page to graphics.”

Blazing a Trail with Software

The reason for all these problems was simple: the FPD shipped well before official support for multiple displays and the accompanying Monitors control panel (which wouldn’t have appeared on the Plus and previous models anyway). Thus Radius had to write their own software to manage this radical peripheral. Larger cursors, a screensaver, double-height menu bars, and other magnification features debuted here, to be further developed as Radius shipped countless color cards for NuBus in the years ahead. Radius even programmed an extension to add Zoom button to the top-right corner of Mac windows which lacked them. Cohen: “Andy’s software teaches most applications to have a ‘zoom box’ (like MacDraw), and cmd-zoom will zoom a window to the full Mac main screen.” The Mac’s screen capture feature also had to be re-written, and even Radius’ own feature only grabbed 90% of the large screen. This software consistently earned rave reviews, and probably explains the leadership position which the company had in the external display market into the 1990s.

The FPD cost $1,995 retail. And for all that money, you only got a 3-month limited warranty!